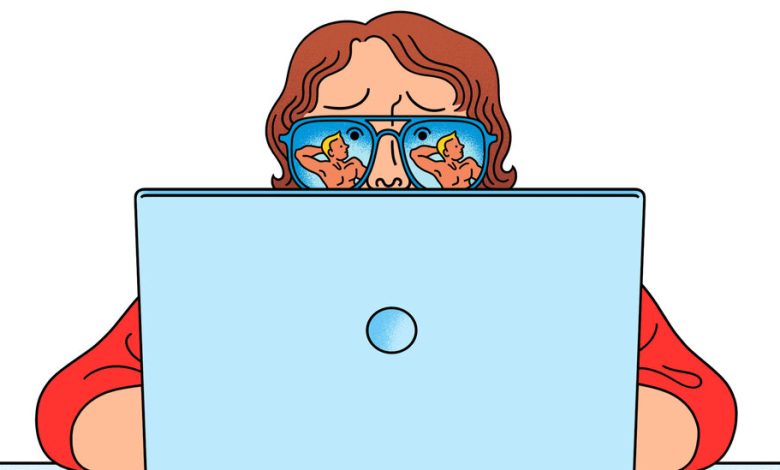

I Just Learned My Son Is a Webcam Model. Should I Be Troubled?

My son, who is in his early 20s, is a college student. He lives on his own, on a modest but ample budget. I have just found out that my son is a “model” on a pornographic streaming service. My initial reaction was shock, revulsion and shame. But the longer I think about it, the more I wonder, is there really anything immoral or otherwise wrong about what he is doing? He does it from the privacy of his home, alone, and seems to earn a substantial amount of money. If he likes what he does, is there any reason on my part to feel alarmed, ashamed, guilty or worried?— R.P.

From the Ethicist:

If your son were being paid for playing the piano, giving dance instruction or reciting poetry via livestreaming — other ways of using his body — nobody would raise an eyebrow, or purse a lip. Sex is seen as special. Viviana A. Zelizer, a sociologist and the author of “The Purchase of Intimacy,” argues that too many people have adopted either a “hostile worlds” model, in which the realm of market exchanges and the realm of intimacy are inherently at odds, or a “nothing but” model, claiming that on some level, all intimacy is transactional. She’s skeptical of both views, and plausibly calls for a finer-grained and suppler perspective. So how are we to think about “camming,” something that’s neither in-person prostitution nor traditional pornography but has features of both?

So far as I can see, your son is neither being exploited nor exploiting others. Some argue that sexual intercourse for hire is wrong, but it would take a separate argument to show that sexual display of this kind was wrong. Even when there’s no concern about exploitation, some social critics, focusing on the “sex” part of sex work, talk about deficits of authenticity and reciprocity. More to the point is the “work” part. Is a digital peep show the best and fullest form of human sexual intimacy? Nobody said it was. It is a performance, which is an asymmetrical activity. What’s really going on in the heads of performers isn’t the audience’s business; what matters is how convincing they are in what they are pretending to feel. A staging of “Romeo and Juliet” is not necessarily made better if the two principal actors are actually in love; real feelings may well get in the way of convincing performances.

If we agree that your son’s camming isn’t wrong, what explains your initial sense of revulsion? Part of your response might arise from the familiar intrafamilial squeamishness about sexual disclosures. That response, then, may have been connected not with what he was doing but with you, as his parent, knowing about it. (You might have reacted very differently if you learned that it was a friend of his who had this sideline.)

But you can also have prudential concerns. How would his prospects be affected if word got out about his webcam gig? Livestreams can be recorded and uploaded. Even if you think that erotic livestreaming is neither wrong nor shameful, it’s natural, as a parent, to worry about how others might react.

Still, your son probably has some sense of the risks and rewards here; he’ll have read up on it via Reddit or the like. Most people who freelance in the sex trade manage to compartmentalize the activity, as the sociologist Angela Jones explains in their book “Camming,” through the use of manufactured identities; they engage in “stigma management” not because they think it’s wrong but because they don’t want to be doxxed or harassed. Sex workers can be at risk of losing their jobs, housing and even children, if they’re identified as sexual performers I.R.L. And then — when they’re in the ordinary meat-space workplace, the realm of Excel spreadsheets and quarterly performance reviews — they may simply not want to be thought of as sexual performers.

There’s nothing hypocritical about compartmentalizing a cam gig. Pretty much all cultures — and subcultures — have ideas about modesty, privacy and discretion, and so understandings about the contexts where erotic display or simply nudity is appropriate. I’m reminded of the old (and doubtless apocryphal) story told about a group of Oxford dons who were sunbathing nude along a sheltered bend of the River Cherwell reserved for the purpose when a boat filled with women suddenly appeared. All the dons scrambled to drape towels around their waists, save for one, who draped his around his head. When his colleagues asked why, he explained, “I don’t know about you gentlemen, but at Oxford I am known by my face.”

Readers Respond

The previous question was from a reader who wondered whether he should tell his best friend’s traveling companions that the friend is bad with money. He wrote: “My best friend has a history of financial ruin. He has unpaid college loans at the age of 50. If he has a credit card, he runs it up to the limit as soon as possible. He owned a business that went bankrupt after two years, leaving the investors holding the bag. He has a low-six-figure salary, consumed by payments on his debts. Now he is telling me he plans to join a group of very affluent friends (he pays his way on his infinite charm and good looks) to visit several countries in Europe this summer. He will be traveling with cash only. Because of his lousy credit rating, he won’t have a credit card. Should I try to convince him to do the prudent thing and decline the trip? … Or should I confidentially warn his fellow travelers — his best (nonromantic) girlfriend is also on the trip — that he might crash and burn, or at least be a nuisance with his ‘special needs’ payment transactions?”

In his response, the Ethicist noted: “Your friend has a serious problem that he ought to address. A financial therapist, who combines coaching about managing one’s finances with psychotherapy to try to unseat these bad habits, might be able to help. You should keep trying to help, too. Given that you know so much about your friend’s financial misadventures, I assume you’ve talked to him about them and offered supportive suggestions for reform. So tell him that if he can afford a fancy European vacation, he can afford a few sessions with a therapist. And yes, you can ask whether it’s wise to spend all this money when he has debts to pay. If he’s undeterred, you can urge him to inform his companions — at least those, like his woman friend, whom he’s close to — that he’s traveling without a credit card, not least because they will have been forewarned if they end up having to come to his rescue. … But warning his prospective traveling companions behind his back? That isn’t how a good friend should behave.” (Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

I pretty much agree with our Ethicist, except that I’d be even more blunt: It’s not the letter writer’s job to tattle on others, nor is it his job to be the nursemaid for these other adults who presumably have agency and should be able to look after themselves. Besides, the letter writer said that his friend “pays his way on his infinite charm and good looks,” so he’s paying his way then. Case closed. — Steve

⬥

The letter writer needs to stop being judgmental. When people don’t have inheritances or other advantages in their background, it’s possible to go into debt for necessities, not just luxuries. — Linda

⬥

I’m afraid it sounds as if this “friend” is more interested in exposing his buddy’s poor choicesthan in helping him or protecting the traveling companions. If they feel his company is valuable enough to subsidize, that is no one else’s business. And, frankly, that dynamic is not uncommon in social situations. — Robbie

⬥

I agree with most of the Ethicist’s response. However, if the letter writer is close to someone in the group, he has a responsibility to warn that person. — Jonathan

⬥

Debtors Anonymous is a 12-step program that addresses the best friend’s issues. I have been a member of this fellowship for over 20 years, and through it I have become responsible with money. It is cheaper than psychotherapy and at least as likely to lead to improvement, if the letter writer’s friend is willing. — Larry